“Mr. Caruso burrows deep – deeper than many audiences may wish to travel – into a profoundly unbeautiful mind.”

The stage is one of the very few places where Joyce Carol Oates’s reputation as a master stylist has suffered a few bruises. Not from lack of effort: The dizzyingly prolific Ms. Oates has written enough adaptations of her own fiction (“Black Water”) as well as original works to fill a few anthologies. Still, for a woman whose name routinely surfaces during Nobel Prize speculation, Ms. Oates the playwright has typically met with responses ranging from tepid encouragement to benign neglect.

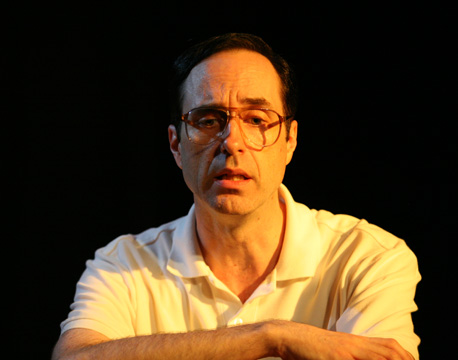

Enter Bill Connington, a reedy, nondescript-looking man in his early middle years who has chiseled her 1995 novella “Zombie” into a disciplined, no-frills, almost unbearably intense solo piece. (It’s one of two Oates adaptations to play at this year’s New York International Fringe Festival, along with “The Corn Maiden.”) Mr. Connington’s mission: Give plausible emotional life to a man whose existence consists almost entirely of torturing and killing teenage boys.

Quentin P_____, a 31-year-old convicted sex offender in a seamy neighborhood of Detroit, is obsessed with turning boys into docile sex slaves. He lures young drifters into his apartment, drugs them, binds them, and attempts to lobotomize them in his bathtub with an ice pick. “To create a ZOMBIE you need to change their brains,” he explains. “Make them more quiet. Make them yours.” The inevitable failure of this plan culminates in his sodomizing the children; the only variation lies in whether or not they have already died at the time.

Ms. Oates’s novella, filled with Quentin’s childlike drawings and bizarre punctuation, is a scouring corrective to “torture porn” films such as “Saw” and “Hostel.” Unlike the lingering sadists of these entertainments (or, more to the point, unlike the creators of these films), Quentin P_____ doesn’t dwell on the protracted, truly awful sufferings of his victims. Only the last victim is ever offered an identity beyond the fairy-tale nicknames he gives them — Bunnygloves, Raisineyes, Squirrel — and this is only because the victim was a neighbor. All they represent to him are a series of fine-muscled young men who fail to meet his needs, to become his zombies. They are excruciatingly alive, at least for a few more hours, but they are dead to him.

Similarly, the meticulously controlled Mr. Connington and his tough-minded director, Thomas Caruso, have jettisoned Ms. Oates’s broader extrapolations of how Quentin’s pathologies are indicative of modern-day society and its morally anesthetizing tendencies. While a few vestiges remain of the sexual humiliations that presumably forged his awful path, Messrs. Connington and Caruso are scarcely more interested in how Quentin got there than he himself is. A tinge of moralism does, however, hover over a new context given to Quentin’s monologue: What began as diary entries have become a sort of confessional that provides at least a glimmer of hope but raises more questions than it answers.

Armed with nothing more than Joel E. Silver’s cadaverous lighting and Josh Zangen’s small handful of props (a table, two chairs, a chess set employed to chilling effect, and a life-size mannequin that is slightly overused), Mr. Connington generates a galvanizing friction between control and abandon. His oversize glasses, clipped delivery, and mirthless grin could easily slide into cliché, but he and Mr. Caruso burrow deep — deeper than many audiences may wish to travel — into a profoundly unbeautiful mind. “My whole body is a numb tongue,” Quentin says of his fruitless sessions with his court-appointed minders; Mr. Connington conveys both Quentin’s numbness and his hunger for any level of intimacy, however warped. As he concludes a horribly graphic rape fantasy with the line “We would eat pizza slices from each other’s fingers,” he is either the most monstrous tragedy or the most tragic monster in recent memory.