For anyone who has ever slammed down the telephone in utter frustration after trying to get an answer from a tech support line, or wasted hours in a hospital basement retrieving an old medical record, or negotiated for months over a 24-cent bank balance that keeps accruing fees because somehow it wasn’t transferred with the rest of an account, or — well, actually, let me start again.

For anyone with a birth certificate, a credit card or a Social Security number, which is to say, in fact, for just about all of us, there will be a flash of instant recognition at the plight of Molly Snyder.

The heroine of Richard Strand’s pointed comedy “Ten Percent of Molly Snyder” has a simple problem: the replacement driver’s license issued after her purse was stolen came with a typo. The play opens with Molly’s arrival at the Department of Motor Vehicles in the not terribly farfetched expectation that her simple problem will be solved in a simple way. But Mr. Strand, who has no doubt called tech support and dealt with bureaucracies and read Kafka, has other plans for her.

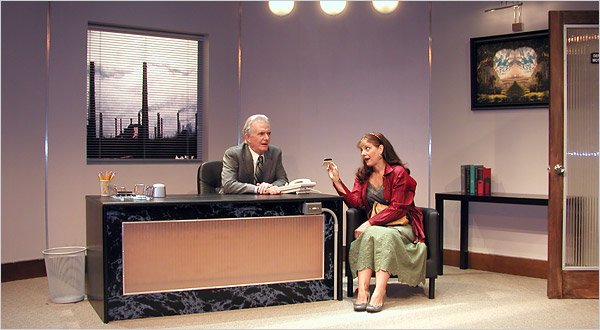

Played by the engaging Liz Zazzi in Penguin Repertory’s smart and snappy production, Molly has landed in the clean-lined, black and beige office of a certain Mr. Aaron, whose zeal for the letter of the law is apparent in every clipped word and precise gesture from the brilliant comic actor Richard Kline. With a monologue that gets the play off to a flying start, Mr. Aaron tries to warn Molly that she’d probably be better off leaving well enough alone:

“You want to tell me about how you were wronged by the system. You didn’t get the service you deserved or you got the wrong thing or you didn’t get enough of something or you got too much of something else — whatever.”

His advice? “Just take whatever it is we gave you and make the best of it.”

Naturally, Molly won’t. She insists that Mr. Aaron fill out the form that will correct the address printed on her license — even though he points out to her that there isn’t actually a form for correcting mistakes that have been made on other forms. The scene crackles with the lively back-and-forth of the best sketch comedy and ends, as it must, with a blackout. Thomas Caruso, the director, establishes just the right terse pace for this exchange. And he manages to keep both Ms. Zazzi, whose zany side was so amply displayed at Penguin in last season’s “Tour de Farce,” and Mr. Kline, best known for his comic flights as Larry in “Three’s Company,” on the straight and narrow path of naturalism. We know the conversation would never happen in quite that way, but the characters seem eminently plausible.

The plausible begins to give way, however, when the lights next find Molly. She is entering the very same office — Ken Larson did the expert set design, Ed McCarthy the first-rate lighting — and the very same person in the very same gray suit (designed by Cindy Capraro) is seated behind the desk. The only things that have changed are Molly’s outfit, the view from the window and the sign on the door. The smarty-pants in the audience will nod sagely and think they’ve gotten the joke: Every office is just like every other office, and the bureaucrats within are equally unconcerned with the difficulties of the little people they are paid to serve.

But Mr. Strand is subtler than that. He ups the ante a little more with each scene, until Molly’s difficulties escalate to levels unimaginable at a local outpost of the D.M.V. To characterize them further would be, well, criminal — and I’ve probably said too much already about a plot that relies heavily on surprise. Even an explanation of the title would spoil some of the fun. Suffice it to say that it’s “The Trial” filtered through “Saturday Night Live”— the kind of darkly topical comedy that once fueled off Broadway but that’s been harder to find lately.

Skillful and entertaining though it is, “Ten Percent of Molly Snyder” could probably benefit from a little more editing. At a mere 85 minutes, it feels ever so slightly long. This probably results from the fact that after three or four blackouts, we begin to sense what will happen next. But Mr. Strand keeps ringing changes on his theme, and eventually Molly’s adventures veer into fantastic territory. That comfortable idea you had at the beginning — that you know exactly what Molly’s going through because you’ve been there — begins to dissipate. Mr. Strand’s blithe satire becomes downright scary. And like all good theater, “Ten Percent of Molly Snyder” will make you think.

The next time someone poses the seemingly harmless question, “Can I help you?” you’re likely to just say no.